A Tale of Three Cities

The following first appeared in WTN News. I had a great time writing it, and enjoyed the feedback it received from readers. You can see the originally published version here. Let me know your thoughts!

____________________________

Quick, spot the similarities: Silicon Valley, New York City, and….Madison, WI? Let's see. Smog levels aren't quite the same. Slight differences in population base, local cuisine, and fashion sense. But at one investment event in Oct. 2009, it was all about the tech.

Biotech, specifically. Life science entrepreneurs in hot pursuit of funding was the focus of the All Things Life Sciences VC forum, in which female biotech start-up leaders vetted by Springboard Enterprises made pitches to investors in three different cities. Madison was first on the road show, followed by Silicon Valley on 10/15 and NYC on 10/30.

Biotech and Regional Economic Development

At first glance, it seemed an incongruous grouping of locales. Not to cast aspersions, but how does Madison - est. population just under 230,000 - measure up to Silicon Valley and New York City? “Madison is an important biotech center,” said Lauren Flanagan, Managing Director of Phenomenelle Angels Fund. In comparison to larger Midwestern cities, Minneapolis is known for medical device companies; Chicago, for general and medical IT; and St. Louis for agbiotech, chemicals and pharma. Madison's niche is arguably still evolving, with strengths in microbial sciences, stem cells, lab research tools, and diagnostics. But in particular, there is growing recognition that in addition to being a good place to grow cell cultures, Wisconsin is a good place to grow early-stage companies.

Business Bargains

“You can get angel funds in Wisconsin, and keep the burn rate low,” says Flanagan. “Having started four companies and having grown up in the Bay Area, what I like about Wisconsin is the rich repository of talent.” Similar sentiments are echoed in irrepressible fashion by Penelope Trunk, who bluntly titled a Brazen Careerist blog post, “Starting a company in Silicon Valley is stupid”. A 2009 salary survey of life science professionals by The Scientist reported that the average Madison salary was, at $63,050, lower than all other U.S. cities for which data was collected aside from Charlottesville, VA. (However, the reader survey did not use random sampling, so it's entirely possible that entry-level or lower-paying public sector scientific positions were overrepresented.) Considering that the Ph.D. density in Madison is among the highest in the nation, one could speculate that the region is a great place to employ skilled talent on the cheap. Small comfort to job seekers, and likely a topic that state and local politicians would rather avoid, but encouraging to firms wanting to stretch their seed money as long as possible.

And certainly, the cost of living in Madison is miniscule in comparison to Silicon Valley and New York City, allowing a far lower salary-induced burn rate for early-stage companies. But the cost of lab and office space also has significant impact on start-up burn rate. Whether leased or owned, lab space in New York City is the most expensive in the nation, and the Bay Area isn't far behind.

When weighing time versus money, shorter commutes also play a role in lifestyle and work productivity. The average work commute in Madison is 16.4 minutes; in the Bay Area, consider yourself lucky to have a commute time at least double that; and NYC? Unsurprisingly, the longest in the nation.

Show Me the Money

However, a lower bottom line doesn't help much if you can't attract funding to begin with. And this is where the dominance of the carefully cultivated Silicon Valley venture capital scene really makes an impact.

“There's more money in one hallway of a VC firm on Sand Hill Road [in Silicon Valley] than in all of Wisconsin, Michigan, and Illinois combined”, says Flanagan. This is not an exaggeration. Venture capital investments in 2002 in the state of California were 145-fold higher than in the state of Wisconsin.

Seed money and initial funding is however possible to land in Madison. “I navigated the boy's club in Madison enough to know there's tons of money here,” said Trunk during a panel discussion at the ATLS forum. And with angel investor support comes invaluable business advice and mentoring. Recently, state support in Wisconsin in the form of the Act 255 Venture Capital Tax Credits program has helped spur funding as well. But it's not enough; the “black hole” of fundraising from approximately $3-$5 million looms large in the Midwest. Entrepreneurs unable to traverse it will see their companies fail. And despite earnest efforts from state and local government leaders and some progress made by groups of angel investors pooling resources and closing bigger deals than individual angels could have undertaken, this is unlikely to change anytime soon. Wealth creation doesn't happen overnight.

Silicon Valley Redux?

During a Gilson Series seminar in February, a provocative question was raised from the audience. Is Madison at a stage similar to 1975-era Silicon Valley, and if so, what transformative events are needed to propel further its development? Joe Kremer, Director of Wisconsin Angel Network, cited the Vision 2020 report produced by the Wisconsin Technology Council as one potential road map, but cautioned, “We're Wisconsin. We're never going to be Silicon Valley…our strategy will be different than those of the coasts. We'll do it the Wisconsin way.”

Certainly, the allure of Silicon Valley lucre is intoxicating to economic development gurus. The problem, points out Darian M. Ibrahim, Assistant Professor at the UW Law School, is that the Silicon Valley scenario is incredibly difficult to replicate. Its history as a high-tech economic powerhouse is relatively short and serendipitous. As late as 1950, the region was most famous as “The Prune Capital of America”. Shifting from an agricultural economy to a technical economy occurred in several stages, the first having more to do with air - radio airwaves, that is - than silicon. Electronics manufacturing exploded in Bay Area just prior to 1970, spurred by specialty firms producing components that found a voracious market in the U.S. defense industry. Interestingly, this early phase of wealth and labor pool establishment (leading to a skilled electronics work force of 58,000 by 1970) didn't rely on heavy-handed guidance from politicians or economic development gurus. It relied on spontaneous proliferation of companies that just happened to have specialty products, the right organizational structure to out-compete everyone else, and an eager market. Money made in the initial stages began to be funneled back into VC investments for later-stage firms in the burgeoning IT field. While the role of technology transfer from Stanford University and other Bay Area academic institutions is often credited with facilitating technology transfer in Silicon Valley, a 2001 analysis by Christophe Leguyer concludes that academic tech transfer played only a small role in the first critical stage of wealth creation.

So, in that respect, public sector efforts to replicate Silicon Valley may be unlikely to achieve the same effect; certainly, other attempts in the U.S. have failed. If true, this may turn out to be disappointing for politicians and economic development leaders in Wisconsin. For example, the Vision 2020 proposal lays out a plan for hand-picking technology clusters across the state and establishing a research arm of “futurists” and leaders to guide tech transfer envisioned as flowing from the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation and the UW System. But will this allow enough flexibility? Arguably, such a plan is more akin to efforts taken in Research Triangle Park in North Carolina, which was inspired by state and local leaders from its inception. But it may not spur the level of explosive growth, market responsiveness, innovation and creativity seen in Silicon Valley.

No Envy for the Big Apple

Still, things could be worse. You could be trying to grow biotech in NYC. As home to Columbia, NYU, Mount Sinai, and Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center among others - not to mention 19 Nobel Prize winners and 39 Howard Hughes Medical Investigators - there's no shortage of research and potential for technology transfer. But while technology transfer offices in NYC institutions have found a niche in making licensing and royalty deals ($791 M in 2007 revenue for NYU alone), the number of spin-off biotech firms that establish within the metro area is astonishingly small - a city-wide total of 21 in 2007 across seven colleges and universities. (For comparison, WARF/University of Wisconsin alone facilitated 6 start-ups in FY2006-2007 and another 6 in FY2007-2008.) The high cost of labor and real estate certainly has a chilling effect on entrepreneurial activity within NYC. But even competition for the relatively low-lying fruit of SBIR/STTR grants has been lackluster. NYC companies landed only 43 SBIR grants in 2006. Wisconsin firms landed 77 in the same year.

Nature and Nurture

One has to wonder how much cultural norms come into play. Is risk tolerance simply higher in the Bay Area than the Midwest, and if so, will this ultimately limit entrepreneurialism in this region? On the flip side, could “West Coast tunnel vision” lead investors there to overlook high-quality opportunities elsewhere? Could a stereotypical hard-driving NYC negotiation style coupled with a desire for fast payoff be behind the push for licensing revenue over entrepreneurialism, which requires far more patience?

And if Midwestern economic development leaders and politicians are to do some difficult self-assessment, how helpful are our deeply ingrained state rivalries? When press releases trumpet the relocation of tech firms within the Midwest, there is a hint of football-induced jubilation: Wisconsin 1! Michigan 0! Score!

But economic growth is likely to require cross-regional collaboration on a far longer timescale than the next political campaign. As Flanagan noted, “There is a need for strategies like funds-of-funds, where private and public capital are invested into regional opportunities, so that there is sufficient follow-on money for entrepreneurial success.” This takes a long view, collaboration, and stomach for risk.

Game on.

Footnotes

In 2004, Forbes Magazine ranked Madison 1st in the nation for Ph.D.s per capita. In 2009,Forbes Magazine ranked Madison 12th for percentage of population age 25 or higher having at least a bachelor's degree.

PriceWaterhouseCoopers/Venture Economics/National Venture Capital Association MoneyTree Survey, 2002

Leguyer C, “Making Silicon Valley: Engineering Culture, Innovation, and Industrial Growth, 1930-1970”, Enterprise & Society 2001 2, 4:666.

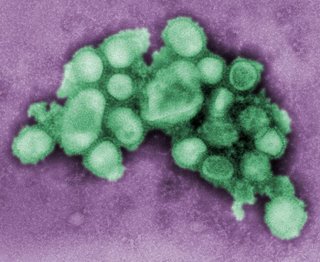

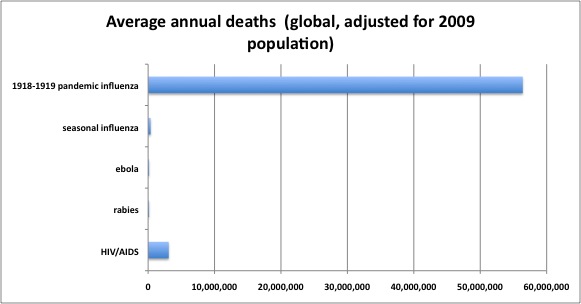

By now, you’ve probably heard something on the news about a new strain of influenza that’s going around. There’s been just a bit of coverage about it.

By now, you’ve probably heard something on the news about a new strain of influenza that’s going around. There’s been just a bit of coverage about it.

February was a blur; I have three or four new posts in various stages of completion, so check back soon. In the meantime, I offer a quote from

February was a blur; I have three or four new posts in various stages of completion, so check back soon. In the meantime, I offer a quote from  For science history enthusiasts, this is a banner weekend. Free events at the University of Wisconsin-Madison campus promise to be fascinating glimpses into the lives of two of the most ground-breaking scientists in history, Galileo and Charles Darwin.

For science history enthusiasts, this is a banner weekend. Free events at the University of Wisconsin-Madison campus promise to be fascinating glimpses into the lives of two of the most ground-breaking scientists in history, Galileo and Charles Darwin. I would have posted this sooner, if not for the urge to hibernate.

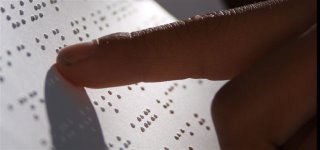

I would have posted this sooner, if not for the urge to hibernate. The holidays often bring news from friends in all corners of the world, and this year was no exception. One of the most fascinating updates was from a friend living in East Lansing, Michigan, where I attended graduate school at Michigan State University. I met her when I was studying at the

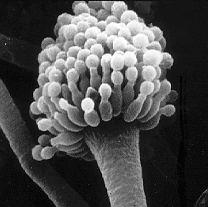

The holidays often bring news from friends in all corners of the world, and this year was no exception. One of the most fascinating updates was from a friend living in East Lansing, Michigan, where I attended graduate school at Michigan State University. I met her when I was studying at the  Take a deep breath. Now, don’t panic, but unless you live in a sterile chamber, you just breathed in between 1 and 100 spores of a killer mold called

Take a deep breath. Now, don’t panic, but unless you live in a sterile chamber, you just breathed in between 1 and 100 spores of a killer mold called  On your Thanksgiving table, consider the cranberry. Especially if you are so lucky as to have freshly prepared cranberry dressing in all its tart and tangy goodness. When you consider what went into getting those garnet jeweled fruits to your table, this unassuming side dish is remarkable.

On your Thanksgiving table, consider the cranberry. Especially if you are so lucky as to have freshly prepared cranberry dressing in all its tart and tangy goodness. When you consider what went into getting those garnet jeweled fruits to your table, this unassuming side dish is remarkable.